Some Diminished Runs Via Slonimsky

In this lesson we’ll do some work with a simple pattern from Slonimsky’s famous Thesaurus of Scales and Melodic Patterns. I’m not going to spend a lot of time explaining what he’s up to in this book — I’ll maybe hit you with the theory in a later lesson. Instead I just want to show you how useful this book can really be by jumping straight in and playing something from it.

For those of you who own a copy of the book, the pattern we’re going to use is number 464. The idea is that it’s a series of minor triad arpeggios that move up in minor thirds, so we get minor triads whose roots follow the notes of a diminished seventh arpeggio. You can use this pattern anywhere where you might use a diminished scale (Half-Whole or Whole-Half) because it contains exactly the same notes, so it works as a fairly mild “outside” sound in many different rock and jazz contexts.

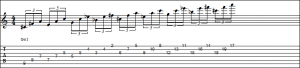

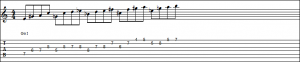

Rather than trying to play it as Slonimsky wrote it I’ve created a variation that happens to sit nicely on the guitar:

To play the pattern descending it’s easiest just to read the tab backwards. You can shift down two more steps at the end to give six more notes — try to work out how to do that to check you understand how the pattern’s put together.

A lot of people look at Slonimsky’s book and see the dots and lines and think “Well, I’m obviously supposed to play exactly what he’s written”. The trouble with this is that it really isn’t what he intended at all. Played as they are, Slonimsky’s patterns sound pretty mechanical and boring. You’re supposed to mess about with them and have fun, so let’s take this pattern and try to figure out a few ideas that work well on the guitar.

Sliding on the top Three String

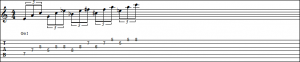

Here’s a variation on the pattern that includes a slide on the highest string (the slide is marked “S” in the tab):

To descend you can use a similar idea with slides on the first string:

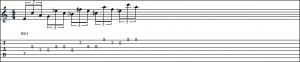

or put the slides on the third string instead:

Finally here’s a version with slides on both the first and third strings:

All of these might be useful exercises for you if you find it hard to slide firmly, accurately and decisively so that the start- and end-notes can be heard clearly. Don’t let them turn into a muddy splurge otherwise the effect is spoiled.

In-Position Versions and Breaking Things Up

You probably don’t always want to be scooting up and down the neck the way we’ve just been doing, so let’s look at some ways to play this pattern within one (or nearly one) position.

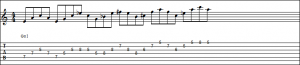

Here’s the basic fingering we’ll use. It requires a bit of preparation because you need to “roll” your fingers across adjacent strings where the notes fall on the same fret. Many people are good at doing this with their index finger, but can you do it cleanly with your little (pinky) finger as this pattern requires? If not that’s a skill worth practicing.

Let’s swap over the second and third notes of the triad each time to create a more angular sound:

This is a simple device for breaking up a pattern that sounds too regular, and it works even better if you play the notes in groups that are different from the number of notes in the repeating part. This idea is explained in more detail in Scott Allen’s lesson “Playing the Odds)”.

So, here’s exactly the same lick as above but played in straight eighth-notes. Play it and listen to the difference in effect — I’ve missed off the last note so you can practice it repeatedly if you like:

Now let’s try exactly the same approach but using groups of five this time. First, here’s the lick with the five-note groups played in a very simple way as quintuplets. Don’t worry if you don’t know how to play quintuplets, just “feel” them in groups of five as they’re written here:

That doesn’t sound very exciting, so let’s play exactly the same notes but in groups of four, which will fox the listener a bit and hopefully make them sit up and take notice:

We can, of course, use the same trick with triplets, which are groups of three, and which also break up the five-note groups:

All of this is about stopping the basic material from sounding like a shallow, mechanical exercise. It’s really not supposed to be that. Maybe there’s just a little bit of one of these licks that you like, and you want to take somewhere else: if so, that’s fine. That’s the kind of thing, I think, that would have pleased the big man himself.

Adding More Notes

Having played around with Pattern 464 for a while we might now want to start adding more notes to it and extending it in other ways. This section includes a few simple licks I came up with but I strongly suggest you try inventing your own as well. We’ll take the position-based pattern from the previous section as the basis of our explorations.

This first one adds the major seventh to one minor triad, the ninth to the next and then repeats the pattern.

This one adds the flat five and changes the order of the other notes slightly:

Finally, here’s a more complicated one involving some slides:

I hope this lesson was interesting and gave you some ideas for constructing your own licks. We guitarists tend to get hung up on technique so much that we forget that note choice really matters as well, perhaps especially in fast runs that can sound like a bland blur unless they have a bit of spice in them. I’ll have more on Slonimsky-like approaches in future lessons.

to find more about Rich, visit his website at http://cochranemusic.com

Powertab 1 / Powertab 2 / Powertab 3 / Powertab 4 / Powertab 5 / Powertab 6 / Powertab 7 / Powertab 8 / Powertab 9 / Powertab 10 / Powertab 11 / Powertab 12 / Powertab 13 / Powertab 14

Powertab downloads to accompany this lesson now up!